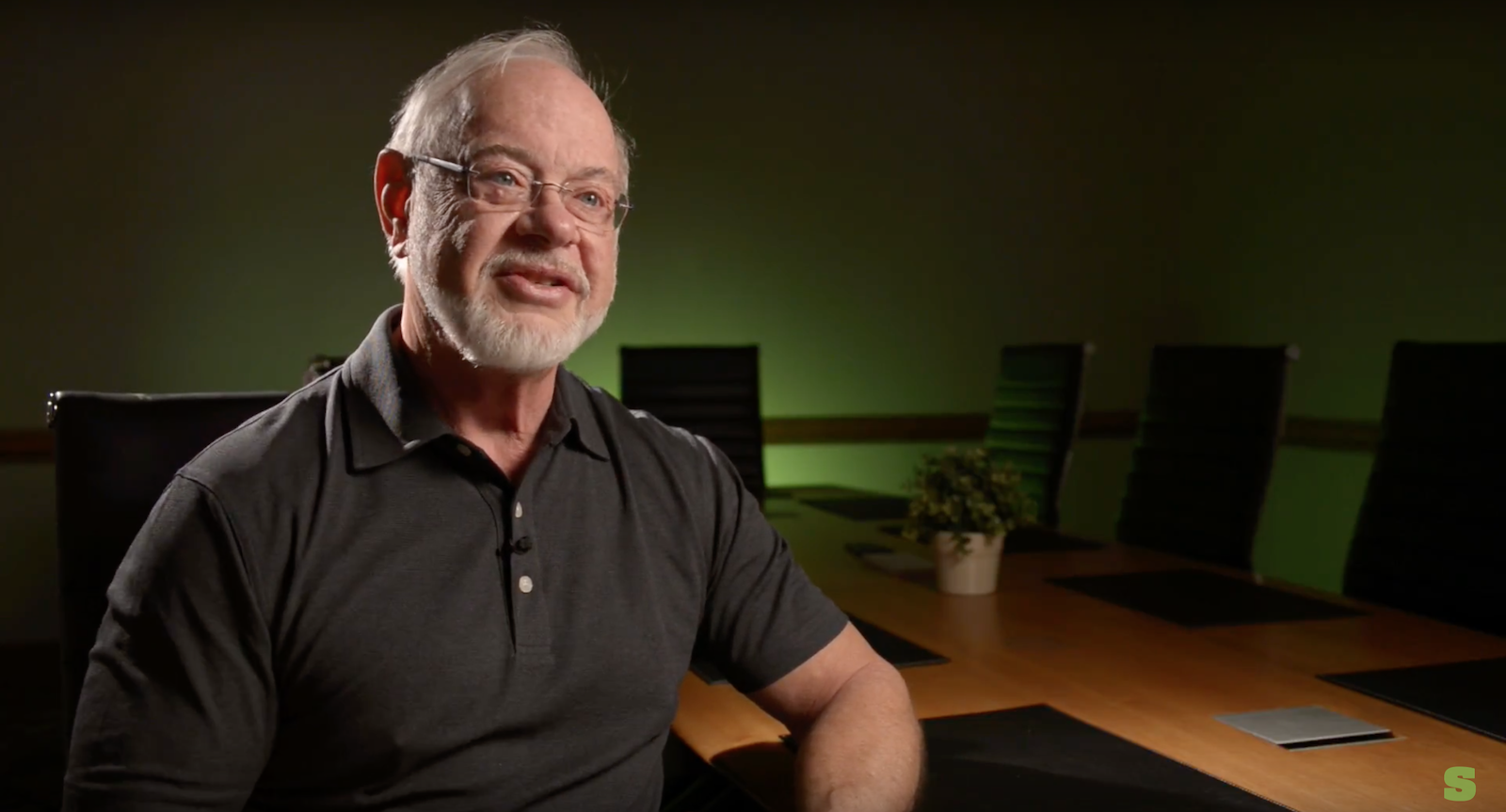

Michael Allen, esteemed e-Learning guru from Allen Interactions, talked to us about the fundamental components of game design that directly translate into good e-Learning principles. Games are all about practice and repetition, this is why gamified learning has become such a massive buzzword within the L&D industry.

His book, “Guide to e-Learning: Building Interactive, Fun, and Effective Learning Programs for Any Company,” arrived in our office recently and has been a fantastic resource for powerful learning design. You can find it on Amazon here: https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/1119046327/.

Transcript

Michael Allen: Games really have always been, I think, an overlooked, valuable platform for instruction.

Practice is so important to almost any valuable skill, and games are all about practice as well. You do the same thing over and over and over again under slightly different conditions, and that’s how you get good at it.

How do you use a game effectively? Because historically when instructional designers decided to try to use a game, they ended up with something that was neither fun nor instructive. Everybody hated it. Everybody hated it. How do you put instructional content into a game format without wrecking the game and still being relatively efficient in terms of instruction?

If you look at what makes a good game, it’s not sound effects, it’s not visuals. The thing that makes a game a good game is good rules. If it has good rules, it’s worth playing. If it has dumb rules, you right away start to think, “This is a dumb game.”

Rules are if-then statements. “If it’s my turn, I get to do one thing.” That’s a rule of play. It turns out that instructional content can be written as rules. “If a customer is returning a product not sold by you, then this is the proper response to give.”

They come together in a funnel very, very nicely, and now you can use game structures built around your content. And all you have to do is instead of writing your content and traditional objectives, you write them as if-then rules: “If this happens, or if you do this, then this consequent happens.”